Poles to Returning Survivors “You Still Alive!” Statements Misunderstood Richmond

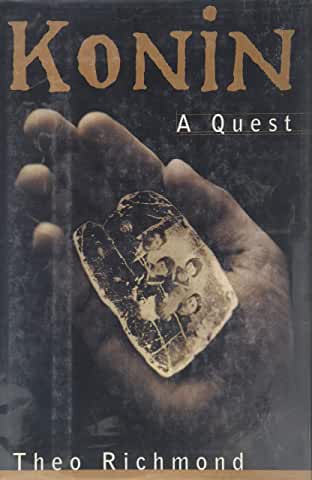

Konin, by Theo Richmond. 1995

Pre-WWII Sunday Closing Laws Demystified. Have “You Still Alive!” Polish Remarks to Returning Holocaust Survivors Been Misinterpreted as Hostility When They Were Not?

If you are interested in various arcane details about Jewish life in the past, this book is for you. This work is from the viewpoint of specifically named Jews in the text, as well as of Jews in general.

Author Richmond interviewed many Jews from Konin who survived the Holocaust, many of whom lived in the USA. He also studied the local archives, and described a few survivors’ visits to the town decades later.

A glossary of Yiddish terms is included. In addition, Richmond explains various terms in throughout the text. For instance, SHEYGETS means “an uncouth gentile”. (p. 45).

This work features a very lucid, and sometimes nostalgic, view of Jewish life in Konin, Poland. The town, situated on the Warta River, was part of the region of Poland directly annexed to the Third Reich following the Nazi German-Soviet conquest of Poland in 1939.

The descriptions of the German cruelties are quite graphic, notably the systematic burning of priceless Jewish books and Torahs. Thousands of local Jews were shot and buried in mass graves near, while others were dispatched to Treblinka.

Unlike most Jewish authors, Richmond departs from a purely Judeocentric view of the events. He provides significant information on the German mass murders of local Poles.

ASPECTS OF JEWISH RELIGION: DISINCLINATION TO ART

Differences between Jews and Christians, in terms of forms of worship, are usually framed in terms of the (perceived) Christian use of graven images. Richmond mentions this, but realizes that the issues are much deeper, (quote) The prohibition of the Second Commandment, the Prophets’ battles with idolatry, the teachings of the rabbis, the cultural and economic traditions of the Ashkenazi Jews, all militated against a fostering of the visual arts. The only reference to painting in the Old Testament is in the context of lewdness and whoredom. [Ezekiel 23:13-16; p.517]. The Jews are not a people of the image. In the synagogue, they press their lips against the word, not an icon or holy statue. (unquote). (p. 122).

[But cannot the accusation of idolatry of images, directed by Jews against Catholics, be turned around, asking if kissing the word is not also a form of worship and therefore idolatry?]

Not surprisingly, the author describes the major Jewish feasts and rites of passage. However, he also discusses lesser-known customs. Consider, for example, the observances of Tashlich at the Warta River, (quote) For centuries the Jews of Konin came to the river’s edge on Rosh Hashanah for the annual ceremony of Tashlich. Facing east, toward Jerusalem, they would turn out their pockets and empty crumbs into the river to symbolize the casting of their sins upon the waters. (unquote). (p. 441).

RECIPROCITY OF PREJUDICES

The Jews who testified about their lives in prewar Poland reported varying experiences with anti-Semitism. Some experienced it, while others stated that they did not. (p. 52). Of course, prejudices went both ways, and the author is candid about this. For instance, a WWI-era religious Jew could end up in a Catholic hospital, where he would experience a Crucifix as follows, (quote)… above the doorway hangs the one-whose-name-must-not-be-mentioned, nailed to the cross. (unquote). (p. 195).

SUNDAY-CLOSING LAWS NOT ONEROUS

Jewish authors have frequently complained that the Sunday closing laws in interwar Poland forced Jews to either violate their Sabbath (Saturday) working, or to be idle two days a week (Saturday and Sunday). Polish authors reply that the laws primarily applied to Jewish enterprises that employed Christians, and that they protected Christians from being put in a position where they would have to either work on Sundays or face negative consequences.

In addition, the laws did not outlaw Jewish occupational labor on Sunday, as long as it was conducted privately or amongst fellow Jews. The experiences of the Konin Jews bears this out, (quote) By law, Sunday was supposed to be a quiet day in the Tepper Marik [Rynek Garncarski], although the food shops were allowed to open in the morning. But behind closed doors, tailors and artisans–unable to afford two days of rest–discreetly carried on working, while merchants caught up with their book-keeping, ignoring the Christian day of rest. It was a world within a world. (unquote). (p. 30).

THE SELF-ATHEIZATION OF POLAND’S JEWS

In 1936, Polish cardinal August Hlond spoke of Jews as freethinkers. Since then, he has been constantly censured for his statement, especially in works that deal with anti-Semitism and Polish-Jewish relations. While none of those interviewed in this book mention Hlond, they do touch on the self-atheization of Poland’s Jews, and essentially validate some of Hlond’s concerns.

Consider the education of Jewish boys. Richmond comments, (quote) For all its failings, the traditional CHEDER did educate. At a time when the surrounding Christian population was largely illiterate, Jewish boys could read by the age of five or six. The CHEDER expressed the Jewish attachment to education and preoccupation with the written word. It produced Jews who could read the Hebrew liturgy and who knew their Bible. As secularization encroached on SHTETL life in the years leading up to the Second World War, the MELAMED’s [teacher’s] authority inevitably declined. (unquote). (p. 47).

Jewish religious worship decreased, and non-religious and anti-religious movements gained in popularity. The author writes, (quote) Unfortunately, there are no sources to draw on for a precise survey of religious observances in earlier times. One can only assume that regular synagogue attendance in Konin remained on a high level until it declined somewhat in the latter half of the nineteenth century under the liberalizing influence of the Haskalah, and dipped sharply after the First World War as Zionism, secularism, and left-wing ideologies tempted yet more congregants away from the religious path. (unquote). (p. 211).

RETURNING JEWISH SURVIVORS, AND POLISH HOSTILITY OR NOT?

There is the Polonophobic meme of the malevolent Pole, angry that some Jews survived the Holocaust, and are now coming back to reclaim the property that the Polish squatters had acquired. Let us examine some basic facts.

Of some 3,000 Konin Jews, only a couple of dozen survived the German Nazi Holocaust. (p. 253). The Holocaust survivors interviewed by Richmond reported various reactions [not only anger!] from Poles upon their return. Interestingly, he remarks, (quote) Questions like “How is it the Germans didn’t burn you too?” asked out of bald curiosity with no ill will intended, struck Jews as hurtful and insensitive. (unquote). (p. 253).

This reminds us that the reactions of certain Poles, though automatically portrayed as malicious in nature in various Holocaust-survivor testimonies and especially in Polonophobic Holocaust lore, were not necessarily so!

To see a series of truncated reviews in a Category click on that Category:

- All reviews

- Anti-Christian Tendencies

- Anti-Polish Trends

- Censorship on Poles and Jews

- Communization of Poland

- Cultural Marxism

- German Guilt Dilution

- Holocaust Industry

- Interwar Polish-Jewish Relations

- Jewish Collaboration

- Jewish Economic Dominance

- Jews Antagonize Poland

- Jews Not Faultless

- Jews' Holocaust Dominates

- Jews' Holocaust Non-Special

- Nazi Crimes and Communist Crimes Were Equal

- Opinion-Forming Anti-Polonism

- Pogrom Mongering

- Poland in World War II

- Polish Jew-Rescue Ingratitude

- Polish Nationalism

- Polish Non-Complicity

- Polish-Ukrainian Relations

- Polokaust

- Premodern Poland

- Recent Polish-Jewish Relations

- The Decadent West

- The Jew as Other

- Understanding Nazi Germany

- Why Jews a "Problem"

- Zydokomuna