Liquor PROPINACJA Exploits Peasants Dynner

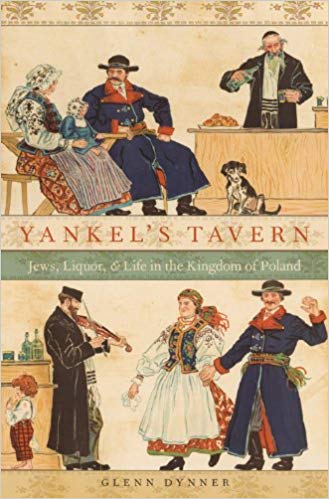

Yankel’s Tavern, by Glenn Dynner. 2013

PROPINACJA: Poland’s Jews and the Liquor Trade—A Very Lucrative Trade—Which Jews Performed and Jews Were Not Forced Into

The author has written a fascinating study that exhibits an obvious attempt at even-handedness. However, in common with many works on this subject, it treats Jews primarily as the servants of nobles and rulers, and devotes insufficient attention to the decision-making freedoms of Jews. The time period of this book is the late 1700’s through the mid- and late-1800’s, the era of Partition and post-Partition Poland.

JEWS FORCED TO BE TAVERN OWNERS? HARDLY

Jews, of course, were not brought to Poland in chains. They came voluntarily, and under the condition that they be welcomed in the role of a merchant class.

Dynner repeats the argument (or exculpation) that Jews became tavern owners under compulsion, in that they usually were denied permission to purchase land, join artisan guilds and professions, etc. (p. 10). This is a chicken-or-egg question–or perhaps it was a reciprocal feedback process. In addition, Dynner undermines his own argument when he later cites the Hasidic tzaddik Menahem Mendel of 18th-century Vitebsk. This tzaddik claimed that the forcible removal of Jewish tavernkeepers was not disastrous, as these Jews simply found new occupations. (pp. 52-53). Were alternative occupations actually unavailable to Jews, it would have been ridiculous for Mendel to make such a statement.

A report involving a government official, Viceroy Jozef Zajaczek (1752-1826), asserted that Jews could find “productive” lines of work but chose instead to maintain their particularism and avoidance of “real” work. (pp. 57-59). Overlooking the “Jews are parasites” mindset exhibited by the report, one must ask how government officials could seriously make statements about Jews in non-tavernkeeping occupations if these were barred to Jews!

In an ironic mirror image of the “Jews corrupt peasants” notion, many quoted rabbis condemned tavernkeeping as an occupation that defiles the Jew and makes it easy for him to circumvent or violate the Sabbath, often in creative ways, and to assimilate and even convert to Christianity. (pp. 55-70). Now, if Jews were forced to be tavernkeepers, what sense would there be for rabbis to condemn Jews for engaging in it?

BIG MONEY IN LIQUOR

Attempts by Poland’s foreign rulers to remove Jews from tavern ownership proceeded in fits, starts, and reversals, over many decades, because liquor concessions were so lucrative (p. 57), and because officials feared the influx of multitudes of unemployed Jews. (p. 54). However, was the latter because Jews were forbidden from performing any other line of work, or was it because the economy could not speedily absorb them, especially in large numbers? The same considerations apply to those many Jews who, during episodes of the banning of Jewish tavern ownership, surreptitiously resorted to unlicensed taverns, Christian-front taverns, and home “taverns”.

TAVERNKEEPING: A JEWISH CHOICE

Towards the end of his book, Dynner stops emphasizing the restrictions that Jews faced, and instead describes many efforts, by Polish and Jewish officials, to “wean” Jews from tavernkeeping. (pp. 153-on). For instance, in 1816, Adam Czartoryski stated that Jews should be evicted from tavernkeeping and settled on land as farmers. (p. 154). For a time, Poles commonly made fun of the thought of Jews as farmers. (p. 154). [Evidently, the Jewish snobbery (quoted below) that dismissed Poles as hopeless drunks and non-achievers was answered by a reverse snobbery among Poles that disparaged Jewish capabilities in agriculture and the military.]

Nevertheless, the efforts began in earnest. Fears of Jewish landowning came later. (p. 155). By 1850, about 5% of Poland’s Jewish population was farmers–a figure that Dynner considers impressive considering the inertia of estate-based societies. (p. 156). The author also acknowledges that Jewish as well as Polish resistance kept more Jews from departing from tavernkeeping. (p. 158).

JEWISH TAVERNKEEPING: IT’S ALL ABOUT MONEY

Finally, in the Conclusion to this book, author Glenn Dynner admits that Jews stuck with tavernkeeping largely because of economic self-interest, (quote) But many Jews could not evidently see why they should renounce a lucrative industry like liquor and enter less lucrative ones like agriculture and army service… (unquote). (p. 174).

THE MYTH OF JEWISH SOBRIETY

Both Poles and Jews recognized the fact that Poles frequently had problems with alcoholism. For Poles, this was a clearly verbalized matter of consternation and shame. (pp. 32-33). [Parenthetically, this refutes the Jews-as-scapegoat thesis. Obviously, at least some influential Poles were willing to take ownership of the Poles’ share of the problem instead of blaming it all on the Jews.]

For Jews, on the other hand, it often became a matter of Jewish elitism. Dynner repeats the following oft-quoted Yiddish ditty, SHIKER IZ DER GOY (The gentile [GOY] is drunk) (quote) “The goy goes to the tavern/ He drinks a glass of wine/ Oh, the goy is drunk, drunk is he/ Drink he must, because a goy is he/ The Jew goes to the study house/ He looks at a book/ Oy, the Jew is sober, sober is he/ Learn he must, because a Jew is he.” (unquote). (p. 45).

Dynner then provides an impressive body of evidence that shows that, although they did not do so as much as Polish peasants, Jews did drink frequently (pp. 31-on). For instance, the religious-inspired drinking of the Hasids was not just an allegation of their adversaries (the Maskilim), but a fact supported by Hasidic sources themselves. (pp. 38-on). Pointedly, Jewish drinking was less overt, (quote) In fact, Polish Jews–particularly Hasidim–indulged in liquor, and sometimes excessively. Their tendency to do so under regulated religious auspices and within Jewish spaces meant that their drinking was less free and visible to outsiders. (unquote). (p. 45).

JEWISH EXPLOITATION OF PEASANTS?

The peasants’ lack of education and emancipation were arguably the root causes of peasant drunkenness. (Reference 46, p. 186). In addition, the tavern was often the only place of entertainment for miles around (p. 18), and furthermore the place upon which the peasant often was dependent for such basics as feedstuffs, horse-carriage repairs, etc. (p. 18).

Dynner realizes that Jewish profiteering sometimes occurred (p. 46) but provides no indications as to how widespread it was. He portrays Jewish tavernkeepers as self-policed, while tacitly admitting that they could take considerable liberties with peasants. He writes, “Most Jewish tavernkeepers were also probably careful not to push things too far. Perhaps few felt bound by their lease contracts’ pro forma moral stipulations, according to which they promised never to cheat customers. And perhaps few were deterred by the risk of fines and prison sentences for serving liquor that was less than the regulation 45 percent alcohol. But each was constrained the knowledge that there was a limit to what the peasant was willing to endure in terms of watered-down vodka, usurious loans, cooked books, and so on.” (p. 28).

Unfortunately, Dynner does not develop the latter theme. How did the Jewish liquor dealer always know how far he could push before the Polish peasant finally pushed back? And what effective recourse did the disadvantaged peasant have–other than violence and pogroms?

JEWISH OR POLISH TAVERN OWNERS: WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

If there is to be any apportionment of blame for the PROPINACJA, Dynner, in spite of his qualifications, apportions it evenly, “Jewish tavernkeepers may not have been the architects of this ghastly enterprise nor even its main beneficiaries, but they were fully complicit.” (p. 26).

The author cites some Poles who condemned Polish Christian tavern owners as harshly as Jewish ones. However, the reader probably realizes that, in general, Jews are more aggressive and successful salesmen than are Poles. For this reason alone, one should suspect that, other factors being equal, Jewish tavern owners are more successful in creating a clientele of alcohol-dependent Poles than are Polish tavern owners.

Apart from this, did it make a difference as to whether the tavern owner was Jewish or Polish? It most certainly did. Dynner candidly remarks, (quote) Many reformers were noblemen themselves, and thus disinclined to blame their peers for placing the “weapon” of liquor in Jewish hands. But some, at least, seemed to genuinely believe that Christian lessees would be disinclined to sell drinks on credit and more likely to have social bonds with their clientele. “The fewer Jewish tavernkeepers there are,” reasoned one reformer, “the less inclined peasants are to get drunk, because the Jewish tavernkeeper sees only the sale of vodka, not his buddy, mate, and best friend with whom he spends time.” (unquote). (pp. 24-25).

Finally, the reader must go beyond the content of this book and appreciate the fact that there is such a thing as a culture of alcohol consumption. This culture can spread. This explains why alcoholism was significant in geographic areas in which there were no Jewish tavern owners as well as in areas in which there were Jewish tavern owners. Finally, a culture of alcohol consumption can persist for many generations. This can explain why alcoholism is significant among Poles even today, even though some generations have passed since the demise of the Jewish-owned tavern in Poland.

THE NOVEMBER 1830 AND JANUARY 1863 INSURRECTIONS

Author Glenn Dynner provides an impressive amount of detail on Jewish support for the Polish insurrections against tsarist Russian rule. At the same time, he is candid about the fact that most Jews adhered to the Talmudic dictum of DINA DE’MALKHUTA DINA–the law of the current kingdom is law. (p. 103). This, of course, meant that Jews generally switched their loyalties in order to support whoever ruled over Poland, or whoever they thought was stronger.

Dynner also attempts to evaluate Jewish conduct against Poland. He cites archival 1830 Uprising figures from the Polish revolutionary regime. When summarized, they show that 83 out of 288 accused spies were Jews. (p. 111). Even though most accused spies were Poles, 83/288 comes out to 28.9%, which, if valid, means that Jews were three times more common among spies than among the general population. [Of course, it is possible that a disproportionate number of Jews was falsely accused of espionage, inflating the quoted Jewish figure. On the other hand, it is possible that Jews, owing to their superior communication skills honed by centuries of experience in commerce, and ability to disguise espionage as commercial interaction, were disproportionately more successful in talking their way out of valid blame for espionage, and/or concealing their espionage in general, thus rendering the quoted Jewish figure an undercount.]

Now consider the 1863 Uprising. Dynner states that the evidence for Jewish espionage is more abundant than that for 1830, and gives many examples of the same. (pp. 122-on).

JEWISH SOLIDARITY, JEWISH COLLUSION, ENDEK BOYCOTTS: DEALING WITH JEWISH ECONOMIC HEGEMONY

As the Polish national movement grew in strength by the late 19th century, proto-Endek and Endek thinkers increasingly contended that Jews work together to drive nascent Polish entrepreneurs out of business, and that only boycotts (and, later, formal discriminatory policies) can “level the playing field” (using modern parlance) by creating significant business opportunities for Poles, and thus emancipating the Poles from Jewish economic dominance.

Although Dynner objects to unqualified notions of Jewish solidarity and Jewish collusion, and cites examples of Jews driving other Jews out of business (p. 147), he tacitly acknowledges that Endek thinking, which he does not mention, did have some basis in fact. He comments, (quote) Contrary to Werner Sombart’s claim that Jews were the first to be committed to the “spirit of capitalism” and the principles of free trade, monopolistic practices and ethnic protectionism were as yet unquestioned in Polish Jewish society. Age-old communal ordinances forbade Jews to compete with and outbid fellow Jews (with limited success, as we shall see)[Have seen], while other ordinances attempted to protect the Jewish community from external competition “lest money fall into non-Jewish hands”…The same ethnic protectionism increasingly prevailed in the liquor trade…the increase in non-Jewish competitiveness was perceived as an act of aggression against the Jewish community, suggesting an economic aspect to the emerging traditionalism. (unquote). (pp. 146-147).

To see a series of truncated reviews in a Category click on that Category:

- All reviews

- Anti-Christian Tendencies

- Anti-Polish Trends

- Censorship on Poles and Jews

- Communization of Poland

- Cultural Marxism

- German Guilt Dilution

- Holocaust Industry

- Interwar Polish-Jewish Relations

- Jewish Collaboration

- Jewish Economic Dominance

- Jews Antagonize Poland

- Jews Not Faultless

- Jews' Holocaust Dominates

- Jews' Holocaust Non-Special

- Nazi Crimes and Communist Crimes Were Equal

- Opinion-Forming Anti-Polonism

- Pogrom Mongering

- Poland in World War II

- Polish Jew-Rescue Ingratitude

- Polish Nationalism

- Polish Non-Complicity

- Polish-Ukrainian Relations

- Polokaust

- Premodern Poland

- Recent Polish-Jewish Relations

- The Decadent West

- The Jew as Other

- Understanding Nazi Germany

- Why Jews a "Problem"

- Zydokomuna