Judeopolonia Nazi German Lublin Reservation Chernow

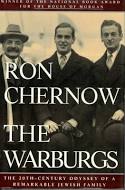

The Warburgs, by Ron Chernow. 1993

Cemeteries are Not Eternal; Lublin Reservation Judeopolonia. German Guilt Diffusion: No Valid Dichotomy Between Germans and Nazis. Nazi Leniency on German Bankers. German “Repentance” Insincere

Author Ron Chernow makes many Jewish-exculpatory statements with regards to the Warburgs, and, in the absence of specialized knowledge, it is difficult for the reader to evaluate them. I focus on some specific issues of current relevance.

A JEWISH-FINANCED JUDEOPOLONIA UNDER NAZI GERMAN AUSPICES

The onetime-proposed Jewish reservation in German-occupied Poland, which was to be located near Lublin, was developed under Himmler as ” The Hamburg Plan”. In this proposed Jewish reservation, Jews could govern themselves. (p. 504). One of its chief proponents was Herr Goettsche, the head of the Gestapo’ s Jewish department for Hamburg. Chernow thus quotes Goettsche, ” ‘ Naturally, the implementation of the project would have to be financed by the Jews themselves. The Warburgs are considered very suitable for that. If they only wanted to do it, the Warburgs in America could raise the necessary money to found such a reservation state.’ ” (p. 504).

The implications are clear. Polish suspicions, about the possible emergence of some kind of Jewish-German agreement at Poland’ s expense, turned out to be based on fact. Had the Lublin reservation come to fruition, it would have placed Nazi Germany and ” international Jewry” on the same side- against Poland!

THE POLISH-RAVAGED JEWISH-CEMETERY MYTH

Recent Holocaust-related programs have falsely painted Poles a heartless, primitive people for not preserving long-abandoned Jewish cemeteries, and for repurposing long-defunct Jewish cemeteries. Let us examine some basic facts- facts that transcend Polish-Jewish relations.

Pointedly, European cemeteries were never ” meant” to be permanent, and this normally applied also to Jewish cemeteries! In fact, Chernow relates a case that is noteworthy precisely because it was the exception to the rule–moreover, an exception that required an intervention, by a prominent Jew, to the highest levels of government. He writes, “In Hamburg, he [Bismarck] responded to Siegmund Warburg” s proposal to create an ” eternal cemetery” . Under Jewish law, bodies are supposed to stay buried in the same spot until resurrection, whereas in Hamburg the Jewish graveyard was freshly dug up every hundred years. When Bismarck approved a new Jewish cemetery near Hamburg, Siegmund asked whether bodies could slumber there for eternity. ‘Certainly’ , replied Bismarck, ‘ as far as it is in the power of the Prussian government to guarantee anything for all eternity.'” (p. 22).

THE PREJUDICES OF GERMAN JEWS AGAINST THE OSTJUDEN

Chernow writes, “The Warburgs also displayed the shortcomings of German Jews. They could be snobbish, arrogant, and status-conscious, especially towards their Eastern European brethren.” (p. xvi). He adds that, “The Russian and Polish Jews often found the German Jews arrogant, cold, and condescending.” (p. 98).

JEWISH BANKERS AND THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

Chernow comments, ” Schiff advanced one million rubles to Alexander Kerensky” s government–a loan he lost six months later when the Bolsheviks came to power. Later, the Nazis blamed Schiff and the Warburgs for having hatched the Russian Revolution when they had merely supported the moderate Mensheviks.” (p. 181). Merely?

Notice that Chernow’ s statements, taken at face value, already admit that leading Jewish bankers were in fact involved in the Russian Revolution. The technicalities are of little relevance. Note, for example, that there was actually little difference between the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks, and these differences centered on personalities and priorities, not tactics and goals. In addition, are we supposed to believe that Warburg and Schiff were really so naive as to believe that the Kerensky government was necessarily stable? Finally, open international Jewish support for the new Soviet government continued long after the Bolsheviks were unambiguously in power.

JEWISH PROFITEERING FROM GERMAN HYPERINFLATION?

It was not necessary for influential Jews to have purportedly engineered the German hyperinflation, for their own selfish benefit, and as demanded by conspiracy theories, in order to profit from its outcome. Nor does it particularly matter if German Jews, as a whole, suffered more from German hyperinflation than did German gentiles. Chernow quips, “Disproportionately represented in private banking, well-to-do Jews were generally better equipped to deal with inflation, while elderly people on pensions and depositors with small banks fared worst. People ravaged by inflation resentfully watched financiers shuffle money into foreign currencies or tangible assets to preserve their capital.” (p. 226).

A JEWISH DOMINANCE OF WEIMAR GERMANY?

Chernow writes, ” In general, Weimar Republic would fulfill Jewish hopes of greater civil equality, ushering in an EXPLOSION OF JEWISH CULTURAL, POLITICAL, AND ECONOMIC ACHIEVEMENT. Jews would advance in the arts, universities, upper civil service, business, and mass media. Unbaptized Jews were finally elected to the Hamburg Senate.” (p. 218; Emphasis added).

What probably most mattered to the Germans was not the magnitude of Jewish influence per se, but the rapidity of its increase. Evidently, that is what animated the pro-Nazi German mentality about the Judaization of Weimar Germany.

THE NAZIS WERE LENIENT ON THE WARBURGS

Interestingly, the Nazis retained the Jewish Warburgs in their positions for some five years after coming to power in 1933. (p. 375; 466-467; 502). And soon after the German-Soviet conquest of Poland in 1939, the Nazi authorities allowed the Warburgs to leave Germany aboard ships that were lit-up in order to alert German attackers that they were neutral. (p. 485). Interestingly, none of the remaining Warburgs perished in the German death camps. (p. 572). Furthermore, two of the Warburgs who were 1st Degree MISCHLINGE (half-Jews), Marietta (p. 512) and biochemist Otto (p. 540), were left unmolested by the Nazis. In fact, Hermann Goering created the fiction that Otto was only a quarter-Jew [2nd Degree MICHLINGE]. (p. 540).

GERMAN DIFFUSION OF GUILT AND GERMAN SELF-PITY. IMPOSSIBILITY OF DICHOTOMIZING GERMANS AND NAZIS

The author’s statements, about German attitudes after WWII, are telling. They contradict the usual exculpatory tale about Nazis and Germans belonging to distinct categories. They clearly were not. Chernow comments, “The Germans cast themselves as innocent victims, dwelling on Allied raids against them instead of their bombing of London, Coventry, Rotterdam, and Warsaw. In a 1946 study by the U. S. Military government in Germany, more than a third of Germans polled still styled themselves a superior race and thought Hitler’ s treatment of the Jews justified.” (p. 581).

Even long after WWII, Germans commonly retained a residual pro-Nazi mentality. Chernow writes, “A report issued by the American authorities in Germany that year [1953] stated, ‘The MAJORITY of the Germans believe that there was more good than evil in National Socialism.'” (p. 594; Emphasis added).

There are further implications to Chernow’s findings. Nowadays, Germans are said to have “repented” of their anti-Semitism, while Poles are said not to have “repented” of their anti-Semitism. Ironic to this rather farcical German-exculpatory meme which, among other things, relativizes anti-Semitism by conflating German and Polish conduct, the reader can see that German “repentance” was rather belated, and more forced by external circumstances than genuine.

To see a series of truncated reviews in a Category click on that Category:

- All reviews

- Anti-Christian Tendencies

- Anti-Polish Trends

- Censorship on Poles and Jews

- Communization of Poland

- Cultural Marxism

- German Guilt Dilution

- Holocaust Industry

- Interwar Polish-Jewish Relations

- Jewish Collaboration

- Jewish Economic Dominance

- Jews Antagonize Poland

- Jews Not Faultless

- Jews' Holocaust Dominates

- Jews' Holocaust Non-Special

- Nazi Crimes and Communist Crimes Were Equal

- Opinion-Forming Anti-Polonism

- Pogrom Mongering

- Poland in World War II

- Polish Jew-Rescue Ingratitude

- Polish Nationalism

- Polish Non-Complicity

- Polish-Ukrainian Relations

- Polokaust

- Premodern Poland

- Recent Polish-Jewish Relations

- The Decadent West

- The Jew as Other

- Understanding Nazi Germany

- Why Jews a "Problem"

- Zydokomuna