Jewish Collaboration Expansive Wolgelernter

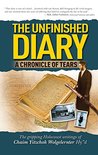

The Unfinished Diary: A Chronicle of Tears, by Chaim Yitzchok Wolgelernter.

Sunday Closing Law. SCHECHITA Law. Prostitution. Draft Dodging. Jewish-Nazi Collaboration Detailed. Nazi-Sponsored Auctions of Jewish Property

This work has the title it does because the author of the diary, Chaim Yitzchok Wolgelertner, did not survive the Holocaust. He was murdered in 1944. The author was an Orthodox Jew. Many of the statement in his diary contain religious themes, and reference the Torah and the Talmud.

The author raises many issues that are directly relevant to Polish-Jewish relations. That is what I focus on in this review.

PRE-WWII POLAND

Dzialoszyce had a Jewish majority, and the author complains that major political positions in the town were filled by government decree, and not by elections, so that Jews would not get them. (p. 35). [However, the reader is not told that, owing to their overabundance in urban areas, Jews would ordinarily get unfair and excessive electoral power. This happened, for example, in the 1912 Duma elections in Warsaw, and in later Jewish attempts to detach the city of Bialystok from Poland.]

Now consider white slavery (prostitution), notably at the international level, and in which Jews were heavily involved. Shlomek Leszman was the owner of several houses of ill repute in Brazil, but was forced to return to Poland because of his various misdeeds. (p. 178). [During the later German occupation, Shlomek Leszman put his business intuition to fruitful use once again. This time he worked with Gestapo-confidante Moshke, and their job was to uncover where Jews were hiding their valuables, and then deliver these confiscated valuables to the Germans after taking their cut. (p. 148)].

I now focus on the Sunday closing law. At Dzialoszyce, at least, it was not widely enforced. Jewish shops would open for Polish shoppers after Mass, and a lookout was posted for the constable. Should he appear, the shops would be hurriedly closed, and he would be bribed to look the other way. (p. 35).

Now consider the 1937 SCHECHITA law. The local butcher started to limit his work to private requests for ritual slaughter. (p. 59). Clearly, the law did not abolish all ritual slaughter.

Attention is now focused on draft dodging by Jews (evasion of military service). Nineteen year-old Meir got a draft notice, in mid-1939. He wrote to his brother Avraham in Canada to express his disappointment with the fact that, despite losing ten kilos, he was accepted into the Polish Army anyway. (p. 59).

Finally, consider atheism, beginning with the secularization of Poland’s Jews. Despite the still-generalized observance of Shabbos, “a great many Jews abandoned their religious observance.” (p. 38). The self-atheization of Poland’s Jews was taking place even in small towns such as in Dzialoszyce, and not, as one might intuitively suppose, only in large, cosmopolitan urban areas. [This tacitly supports Polish Cardinal Hlond’s much-condemned 1936 statement, in which he referred to Jews as freethinkers.]

JEWISH COLLABORATION WITH THE NAZIS: NOT JUST CHOICELESS CHOICES

Some commentators have argued that Jews who served the Nazis were not really collaborators, because they received no favors from the Germans. This is clearly incorrect. For instance, the Chairman of the Slomniki JUDENRAT, Bialabrode, regularly fraternized with the Nazi Bayerlein, who was the newly-appointed chief of the Miechow SD. The Nazis gave Bialabrode an automobile for his use. (p. 160). The author adds that, (quote) He [Bialabrode] carried a leather whip with him all the time and struck innocent Jews no differently from a Gestapo agent…During the deportations in the Miechow district, Bialabrode was granted an extraordinary level of authority by Bayerlein… (unquote). (p. 161).

Moshke, another Jewish Nazi collaborator, worked with Kowalski, the Polish chief of the Miechow secret police. Moshke identified the secret hiding places, of the Jewish valuables at Dzialoszyce, and relayed them to Kowalski, who arranged for the hiding places to be torn open and the wealth confiscated. (p. 177). Moshke then bought the valuables from Kowalski for a fraction of their value. (p. 178).

The author described the infamous Jewish Police, the ORDNUNGSDIENST, as follows, (quote) Its men pandered to their German masters and distinguished themselves by implementing every decree and ordinance with the sort of cruelty exhibited by newly trained Gestapo officers. Indeed, during the Dzialoszyce expulsion raid, they did not sit with folded hands. If ever there will arise a Jewish historian who will record the events of these days, his face will turn red with shame when he reaches the disgraceful chapter of the ORDNUNGSDIENST. (unquote). (p. 459).

The editors explain why military Jewish resistance, as in the case of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, was not much more common, (quote) They [the Jews] were expecting to buy their survival by paying a fortune in goods and money. (unquote). (p. 330). [This spirit of obsequies to the Germans tended to reinforce the notion of “Jewish passivity”, and furthermore made it difficult for Poles to take seriously the Jewish requests for arms for eventual combat against the Germans.]

The tendency of the JUDENRAT to try to ransom the Jews was, of course, predicated on their authority to collect money from the community, and this had untoward consequences, (quote) On more than one occasion, the JUDENRAT took advantage of an opportunity to help the town by extorting money for their own purposes. (unquote). (p. 463).

Some of the Dzialoszyce-area Jews were sent to German labor camps. Interestingly, the overseer of one of those camps was Stieglitz, a German Jew. (p. 173).

POLISH CONDUCT–NOT BLACK AND WHITE

It appears that, unlike most Jews of German-occupied central Poland, the Jews of the Dzialoszyce area died in local Einsatzgruppen-style mass shootings and local burials, and not mass gassings and cremations at distant death camps. Wolgelertner’s work does not support the characterization of Poles habitually delighted in Jewish sufferings. In fact, most Poles displayed empathy, prayer, and crying as the Dzialoszyce-area Jews were taken away by the Germans to be shot. (p. 110, 119, 181, 201).

The actions of the POLICJA GRANATOWA (Polish Blue Police) also cannot be generalized. They are known to have been unwilling to shoot Jews (p. 323), and to free captured Jews when paid a bribe. (p. 293). As for the mass shootings of Jews, the non-German participants were Ukrainians. (p. 174).

Some Poles entrusted with Jewish belongings did not return them later to the Jewish owners. Others did. (pp. 415-416).

Author Wolgelertner rejects the common Polonophobic generalization that would have us believe that Poles were disgusted to learn that some Jews had survived. He comments, (quote) To be fair, some kindhearted Polish neighbors were genuinely happy to see us. (unquote). (p. 416).

THE NAZI AUCTIONS OF JEWISH PROPERTY

Neo-Stalinist authors, such as Jan T. Gross and Jan Grabowski, have painted a lurid tale of “greedy” Poles coming to Nazi-sponsored auctions of Jewish property. Apart from the fact that, far from being greedy, the Poles were living in crushing poverty, the property-buying situation was not so clear-cut.

Some local Poles took part in such auctions, while others did not. In fact, the Poles around Dzialoszyce came to the soon-to-be-doomed Jews and offered to buy their property in advance, for this reason, (quote) “We have your benefit in mind,” they explain. “If you sell us your possessions, at least you’ll get some money out of it. With public auctions taking place all over, what do the Jews gain by leaving their things behind?” (unquote). (p. 181).

The auction of the remaining belongings of the Jews of Dzialoszyce eventually took place. The Polish farmers of Szyszczyce refused to take part. (p. 221).

Ironically, one of the chief duties, of the earlier-discussed Jewish collaborator Bialabrode, was to empty Jewish houses of valuables so that they could be shipped to the Reich—all done so that the property would not get auctioned off and fall into the hands of the Poles. (p. 161).

FUGITIVE JEWS IN PROLONGED HIDING

Large groups of fugitive Jews could be in hiding, for significant amounts of time, without being denounced. For example, over sixty Jews hid among Poles at Szyszczyce. (p. 221). A cave behind Tetele’s field was the shelter to over thirty people, and the local Poles thought it a religious duty to bring them food and other provisions. (pp. 285-286).

Another group of Jews hid in a MIKVEH building. Their presence was an open secret among the Poles: Even children talked about them. Yet no one denounced them. After being warned about the common knowledge of their existence, these Jews moved to a more secure location two weeks later. (p. 234).

Neo-Stalinist Jan T. Gross and his emulators have belittled the German-imposed death penalty for the slightest Polish aid to Jews. In contrast, Wolgelertner, who actually went through the Holocaust, does not. (e. g, p. 121, 218, 221, 226, 294, 300, 367, 468). In fact, in several of the cases he sites (e. g, p. 367), the Polish benefactors were so terrified by the nearby German killings of other Polish benefactors that they evicted the Jews they were hiding. To add to the terror, the Germans also threatened to burn down entire Polish villages for individual Poles hiding Jews. (p. 221).

FACTORS IN THE NON-SURVIVORSHIP OF FUGITIVE JEWS

This work makes obvious that there were many reasons that fleeing Jews did not survive—other than the oft-accused and much-exaggerated Polish denunciations and killings.

The Germans did not need Polish informers to find Jews. They conducted house searches for Jews in hiding among Poles. (p. 299). The Germans intentionally spread false rumors, about Jews being allowed to gather in certain “sanctuary towns”, in order to lure Jews out of hiding. (p. 223). The Germans conducted LAPANKAS in order to kidnap Poles for forced labor. In doing so, they often came across hidden Jews. (p. 226). Finally, many Jews, exhausted from living as fugitives, gave up, and turned themselves in to the Germans. (pp. 282-283).

JEWISH BANDITRY PROVOKES POLISH REPRISALS

Poles denounced or killed Jews they knew or suspected were stealing from them. This work provides some examples of the latter.

One evening, Moshe Rederman, the butcher, instead of buying food, and without telling anyone, slipped into a Polish neighbor’s storage room to get some flour. A Pole saw him, followed Moshe to his hideout, and informed the Polish Police. (p. 234).

Chaim Yitzchok Wolgelernter ate kosher foods while in hiding, and his Polish benefactor, Biskup, supplied them. (p. 370). Years later, Abraham Fuhrman described how Wolgelernter reacted to food, that had, under different circumstances, been acquired by banditry, (quote) When Chaim Yitzchok witnessed our methods of extorting provisions from the Poles, he himself was loath to eat the food, but at the same time he said to me in a fatherly way, “MEIN KIND, ESS GEZUNTERHEIT—eat in good health, my child.” (unquote). (p. 370).

LOCALS’ KILLINGS OF JEWS

Even when fugitive Jews were killed, there was usually no way to verify the identity and/or motives of the killer(s). For instance, the Pole Biskup, an erstwhile benefactor of Jews, was thought to be a man of dubious character, and was therefore suspected of killing a Jew. However, other Jews pointed out that the killers could actually have been Polish partisans, or bandits. (p. 436).

The author points to the killing of Avraham Szajnfeld, who had been lured into an ambush and drowned. He tells us that the Poles did this because they “could not swallow the idea that a Jewish survivor had become a government official”. (pp. 418-419). How about the elementary fact that he was executed because he was serving the Soviet-imposed Communist puppet government?

AN ALL-TOO-FAMILIAR POLONOPHOBIC WHOPPER

A group of Jews travelled to the Dzialoszyce area, in 1993, to locate and exhume the skeletal remains of their loved ones. They were eventually successful. After being told by some peasants that they must pay for the trees they had uprooted, and being reminded of what had once taken place at Auschwitz, one of them wrote, “I learn firsthand that my mother and other Holocaust survivors were not exaggerating when they maintained that the prevalent, virulent hatred towards Jews was transmitted through the generations in mothers’ milk.” (p. 445). [Years earlier, Yitzhak Shamir, the Prime Minister of Israel, had made a very similar statement. Evidently, it is a fairly common trope in Jewish thinking. The generalization is as racist as saying that Jews imbibe greed and unscrupulousness with their mother’s milk!]

To see a series of truncated reviews in a Category click on that Category:

- All reviews

- Anti-Christian Tendencies

- Anti-Polish Trends

- Censorship on Poles and Jews

- Communization of Poland

- Cultural Marxism

- German Guilt Dilution

- Holocaust Industry

- Interwar Polish-Jewish Relations

- Jewish Collaboration

- Jewish Economic Dominance

- Jews Antagonize Poland

- Jews Not Faultless

- Jews' Holocaust Dominates

- Jews' Holocaust Non-Special

- Nazi Crimes and Communist Crimes Were Equal

- Opinion-Forming Anti-Polonism

- Pogrom Mongering

- Poland in World War II

- Polish Jew-Rescue Ingratitude

- Polish Nationalism

- Polish Non-Complicity

- Polish-Ukrainian Relations

- Polokaust

- Premodern Poland

- Recent Polish-Jewish Relations

- The Decadent West

- The Jew as Other

- Understanding Nazi Germany

- Why Jews a "Problem"

- Zydokomuna