ARMIA KRAJOWA Why Few Jews Hilberg

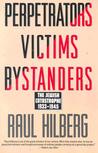

Perpetrators Victims Bystanders: The Jewish Catastrophe 1933-1945, by Raul Hilberg. 1900

Polish Blue Police Not Collaborationist. Why Few Jews in ARMIA KRAJOWA. Holocaust “Church Silence” Myth

Raul Hilberg has written a generally balanced and thoughtful account. The only obvious shortcoming of this book is his over-reliance on tendentious sources of information (such as Claude Lanzmann’s SHOAH, and Communist Shmuel Krakowski).

Hilberg discusses several collaborationist governments under Nazi Germany. He also points out that, by July 1, 1942, eighteen Ukrainian Schutzmannschaft battalions alone were in existence (p. 95). The Baltic nations provided a comparable number of collaborationist police battalions and many more officers (p. 97).

POLISH BLUE POLICE (POLICJA GRANATOWA) NOT COLLABORATIONIST

The recent over-attention to the Jedwabne massacre has generated a greatly exaggerated notion of Polish-German collaboration, and the Polish Blue Police (the Policja Granatowa) has often been falsely conflated with the Ukrainian and Baltic collaborationist forces. Hilberg corrects this: “Of all the native police forces in occupied Eastern Europe, those of Poland were least involved in anti-Jewish actions…The Germans could not view them as collaborators, for in German eyes they were not even worthy of that role. They in turn could not join the Germans in major operations against Jews or Polish resisters, lest they be considered bytraitors by virtually every Polish onlooker. Their task in the destruction of Jews was therefore limited.” (pp. 92-93).

Hilberg’s notion of “worthiness” is puzzling because, in spite of Hitler’s objections (p. 93), the Ukrainian Schutzmannschaft battalions were nevertheless formed. The Ukrainians were regarded as Slavic untermenschen (subhumans) no less so than the Poles! The acceptance of Jewish collaboration (e. g., the infamous ghetto police), in spite of any trace of “worthiness” attributed to Jews by the Germans, needs no comment.

JEW-KILLING BECAUSE OF BANDITRY

The draconian German occupation had caused near-starvation conditions in the countryside, putting local Poles and fugitive Jews in conflict. Hilberg realizes that Polish killings of Jews were at least sometimes motivated by this: “Food, and everything else they needed, had to be acquired or taken somewhere. One German account noted that Polish peasants, about to be attacked by Jewish ‘bandits”, had beaten thirteen of them to death.” (p. 208).

EMOTIONAL ISSUES ADDRESSED

Hilberg is unafraid of provocative issues. He is candid about the Zydokomuna: “Jews, alongside a number of other non-Russians, had taken a leading part in the Communist revolution.” (p. 250). He tackles the issue of overall Jewish passivity in the face of Nazi slaughter as follows: “In the Jewish councils, no pamphlets were composed and no arguments were made to show that any German action was hurtful and morally wrong. No ill will was expressed to the Germans. No threats were made to the life of any German. No rumors were started that the Allied powers would retaliate for the destruction of the Jews.” (p. 178).

WHY FEW JEWS WERE IN THE ARMIA KRAJOWA

Hilberg has a good grasp of the actual reasons for the under-representation of Jews in the mainstream Polish Underground Army (the AK): “Many members of the Armia Krajowa were civilians during the workday and underground soldiers only on weekends and at night. The Jews, on the other hand, did not and could not have regular jobs or occupations as fugitives. For the Armia Krajowa it was important to wait for a decisive moment of German weakness to seize portions of Poland, or at least Warsaw, and to secure such a foothold before Soviet forces could arrive. In the meantime, it hoarded its weapons with the thought that it had fewer arms than men. All too often the Jews presented themselves instead as additional men without rifles, pistols, or military training. If, in addition, they were poor speakers of Polish or recognizably Jewish, their handicaps made them a self-evident liability” (p. 207).

WARSAW GHETTO UPRISING FACED JEWISH OPPOSITION

Interestingly, and despite the imminent destruction of their Jewish communities, some Jewish leaders agreed with the overall Polish underground combat strategy: “The Socialist Bund leader Maurycy Orzech strongly believed that Jews should not fight a battle separate from the Poles; the time had not yet come.” (p. 184).

DESPERATE HOUSING SHORTAGE SOMETIMES MADE POLES RELUCTANT TO RETURN JEWISH PROPERTY

The acquisition of post-Jewish properties by Poles has recently gotten a great deal of one-sided media attention through the publication of FEAR by Jan T. Gross, and this has been misrepresented as an outcome of Polish greed. In actuality, there was a desperate housing shortage in Poland during (and after) the war. Hilberg touches on this: “Despite gains of space as a result of ghetto formation, the Poles were still crowded. Polish Warsaw (population 1 million) was lacking 70,000 apartments…In the city of Radom, the norm was a room density of six for Jews, and three for Poles.” (p. 312).

THE MYTH OF CHURCH “SILENCE” ON THE HOLOCAUST

Hilberg has a realistic understanding of the impotence of the Christian church in saving its own, let alone of saving the Jews, from German actions: “The churches, once a powerful presence on the European continent, had reached a nadir of their influence during the Second World War…Even in the democratic west, churches were subordinate structures, regulating the lives of citizens mainly on Sundays, and then only in a ceremonial manner…If the protection of baptized people was problematical, any attempt to help professing Jews was to be even less promising.” (p. 260, 262).

HOLOCAUST, AND THEN THE POLOKAUST

Citing German documents, Hilberg notes that Poles believed that they would be “next” (pp. 204-205) when they saw the Jews being taken to their deaths. He also writes: “In Poland, the local German administrators would order the Polish population to stay indoors and keep the windows closed with blinds drawn during roundups of Jews…” (p. 215). In various contexts, Hilberg (p. 136, 147, 160) repeatedly refers to the fact that Jews about to be deported to their deaths were told that they were being “resettled”. However, Hilberg fails to make this connection with the Germans’ stated eventual aim of “resettling” the Poles and other Slavs. Nevertheless, Hilberg does move beyond the genocide of Jews to the planned long-term genocide of Slavs: “There was some hope that Slavic populations in German-occupied Europe could be brought to extinction by mass sterilizations.” (p. 67).

To see a series of truncated reviews in a Category click on that Category:

- All reviews

- Anti-Christian Tendencies

- Anti-Polish Trends

- Censorship on Poles and Jews

- Communization of Poland

- Cultural Marxism

- German Guilt Dilution

- Holocaust Industry

- Interwar Polish-Jewish Relations

- Jewish Collaboration

- Jewish Economic Dominance

- Jews Antagonize Poland

- Jews Not Faultless

- Jews' Holocaust Dominates

- Jews' Holocaust Non-Special

- Nazi Crimes and Communist Crimes Were Equal

- Opinion-Forming Anti-Polonism

- Pogrom Mongering

- Poland in World War II

- Polish Jew-Rescue Ingratitude

- Polish Nationalism

- Polish Non-Complicity

- Polish-Ukrainian Relations

- Polokaust

- Premodern Poland

- Recent Polish-Jewish Relations

- The Decadent West

- The Jew as Other

- Understanding Nazi Germany

- Why Jews a "Problem"

- Zydokomuna